17th Century Warship Vasa: The Bizarre Journey From Watery Grave to National Treasure

- Peter Deleuran

- May 14, 2023

- 8 min read

The warship Vasa, Djurgården, Östermalm, Stockholm, Sweden. 31 December 2012 (Source: Wikimedia Commons Image has been subjected to color change).

In the early 17th century, Sweden was a rising power in Europe, and its king, Gustavus Adolphus, was eager to build a fleet of warships to protect his country's interests. The most ambitious of these projects was the Vasa, a massive, ornate vessel that was to be the pride of the Swedish navy. However, the ship's story was to end in disaster, as it sank on its maiden voyage in 1628.

Part 1: Building the Vasa The Vasa was conceived as a symbol of Sweden's growing power and prosperity, and no expense was spared in its construction. The ship was to be the largest and most heavily armed vessel in the Swedish navy, and its design incorporated the latest innovations in shipbuilding technology. It was commissioned by Gustavus Adolphus in 1625 and was built in the naval yard at Stockholm.

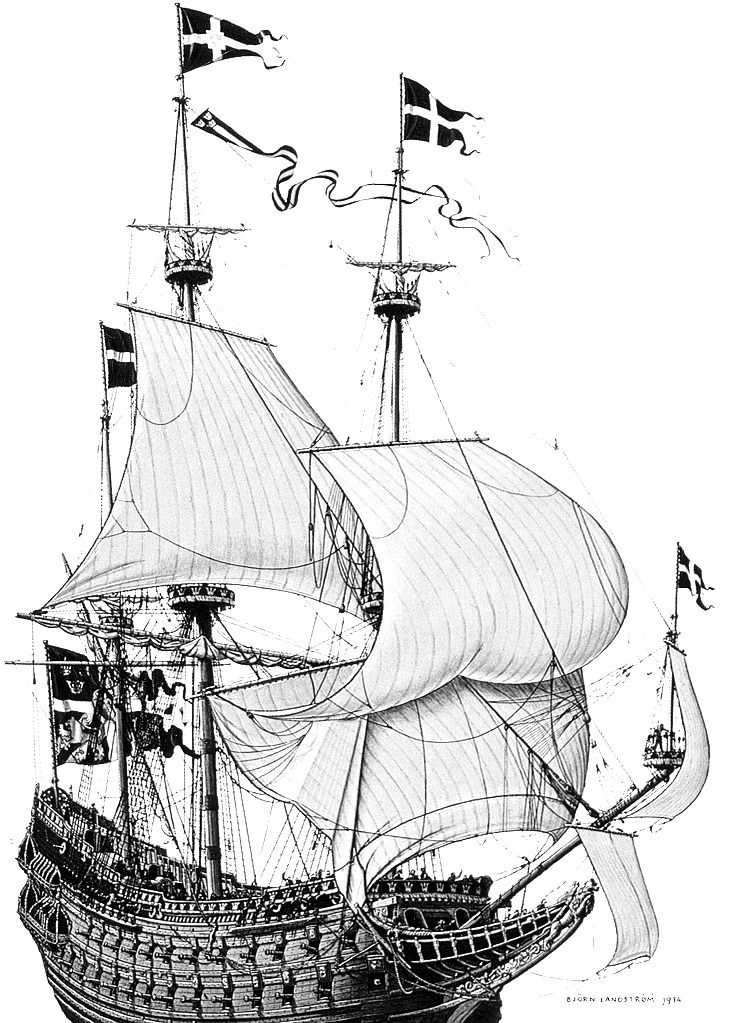

Painting of the Swedish warship Vasa by Björn Landström (1917–2002). (Source: Wikimedia Commons).

Construction of the Vasa was overseen by the Dutch shipbuilder Henrik Hybertsson, who had been recruited by the Swedish king himself to build the ship. Hybertsson was an experienced shipbuilder who had worked on some of the most advanced vessels in the world, and he was tasked with bringing the latest in shipbuilding technology to Sweden.

The Vasa was to be a massive ship, measuring 69 meters in length and 48 meters in height. It would be armed with 64 bronze cannons and capable of carrying a crew of over 400 men. The ship was built using a technique known as "edge-fastened" construction, which involved fastening the planks of the ship together using metal bolts and wooden pegs. This technique was common in shipbuilding at the time and was considered to be a reliable method of construction.

In the early 17th century, Sweden was busy building an empire around the Baltic Sea in northern Europe. A strong navy was essential. During the 1620s Sweden was at war with Poland. In 1625 the Swedish king Gustavus Adolphus ordered new warships. Among them the Vasa. (Source: Wikimedia Commons).

The ship was embellished with a lavish array of ornate carvings and decorations. The stern of the ship was adorned with a large sculpture of the Swedish lion, flanked by two mermaids. Additional dozens of other carvings, including figures of Roman emperors, cherubs, and mythological creatures were scattered aboard displaying the epitome of contemporary craftsmanship.

The stern of a 1:10 model of the ship Vasa on display at the Vasa Museum in Stockholm. The photo shows the colors scholars believe were used for the sculptures on the original 17th century ship. (Source: Wikimedia Commons).

Construction of the Vasa took nearly two years and was completed in 1627. The ship was allegedly an impressive sight, towering over the other vessels in the Stockholm harbour and was supposed to be a shining symbol of Sweden's growing power and a testament to the country's ability to compete with the great naval powers of Europe.

In spite of its impressive size (and ornate decorations), the Vasa was not a well-designed ship. The ship's centre of gravity was far too high, making it dangerously unstable. This was partly due to the weight of the ship's guns, which had been added to the design at a late stage. The ship's designers had also made several other mistakes in the ship's design, including making the base of the ship too narrow and the sides too tall. These design flaws would ultimately prove fatal.

The Sinking

On August 10, 1628, the ship was scheduled to embark on its maiden voyage from Stockholm's harbour. Many people had come to see the ship off, including members of the royal court, sailors, and civilians.

The ship was fully rigged and manned, and her sails were hoisted in anticipation of departure. The Vasa was supposed to make its way down the harbour and out to sea, where it would begin a series of test runs to measure its seaworthiness and capabilities.

As the ship began to move, however, it quickly became apparent that something was wrong. A light breeze filled the sails, but the ship began to lean dangerously to one side. Despite the efforts of the sailors and officers, the ship continued to tilt.

Model showing the sinking of the Vasa in 1628. (Source: Wikimedia Commons).

The Vasa had only travelled about 1,300 feet when it heeled over to an alarming degree. Water flooded in through the open gunports, causing the ship to become unstable and tip over. The sails and rigging dragged into the water, and the Vasa began to sink quickly. Panic broke out among the passengers and crew, who scrambled to escape the rapidly sinking ship.

Despite the efforts of some of the sailors to lower the ship's boats and rescue those on board, many were trapped below decks as the Vasa rapidly filled with water and sank to the bottom of the harbour. It is estimated that between 30 and 50 people died in the disaster, including sailors, soldiers, and civilian passengers.

The sinking of the Vasa was a shocking and humiliating event for the Swedish navy and the royal court. The ship had been intended to be a symbol of Sweden's power and prowess, but instead, it became a symbol of failure and incompetence. The disaster caused significant damage to the reputation of the king and his advisors, who were heavily blamed. Part 2: The Investigation and Salvage of the Vasa After the sinking of the Vasa, an investigation was launched to discover the cause of the disaster. The Swedish king ordered a commission to be formed, which was made up of naval officers, shipbuilders, and experts in naval architecture. Their task was to examine the wreckage of the ship and determine what had gone wrong.

The commission interviewed surviving crew members and examined the ship's plans and construction. They found that the Vasa had a number of design flaws and errors in construction that had contributed to the ship's instability.

One of the main factors in the Vasa's sinking was due to its high centre of gravity. The ship was top-heavy, with a large number of heavy cannons mounted on the upper deck. This made the ship prone to tipping over in even moderate winds. Additionally, the ship's hull was too narrow, making it unstable and prone to rolling in rough seas.

A model of Vasa's hull profile, taken at the Vasa Museum. (Source: Wikimedia Commons).

Another contributing factor was the placement of the gunports on the lower deck. The gunports had been built too low in the hull, which allowed water to flood in through them when the ship heeled over. The crew had also neglected to close the gunports when the ship was being loaded, which made the ship even more unstable.

The investigation into the sinking of the Vasa was groundbreaking in many ways. It was one of the first recorded instances of a forensic investigation into a marine disaster, and it helped to establish the importance of careful ship design and construction. The commission's report led to significant changes in shipbuilding practices, including the adoption of new methods for calculating stability and the design of ships with lower centres of gravity. The commission's report was a damning indictment of the king's decision-making and the lack of expertise of his advisors. It was clear that the sinking of the Vasa was a result of a combination of factors, including overconfidence, poor planning, and a lack of understanding of the principles of naval architecture.

New research based on archaeological discoveries suggests that a big reason for the sinking could be that the mix of Dutch and Swedish craftsmen employed had used different rulers. Archaeologists have since uncovered four measuring instruments used by the shipbuilders, with two calibrated in Swedish feet of 12 inches, and the other two measuring Amsterdam feet of 11 inches. As a result of using distinct measurement systems on opposite sides of the vessel, its weight was unevenly distributed with a greater mass towards the port side.

The Vasa in the 17th and 18th Centuries In the immediate aftermath of the sinking of the Vasa, the ship was largely forgotten. Only 50 of the guns were salvaged. It was seen as a symbol of the king's foolishness and was quickly buried under layers of mud and debris. It wasn't until the 19th century that the ship began to attract attention again.

Principle sketch showing how it might have happened when a large part of Vasa's cannons were salvaged in the 17th century with the help of a diver's bell. In 1664, Albreckt von Treileben and Andreas Peckell salvaged Vasa's cannons. Using the diver's bell, the two managed to bring up more than 50 guns. (Source: Picryl).

In the 1860s, a group of Swedish historians and archaeologists began to excavate the site of the Vasa's sinking. They uncovered the remains of the ship and were amazed at its remarkable state of preservation. The discovery of the Vasa's wreckage sparked a renewed interest in the ship, and it quickly became a symbol of Sweden's rich naval history.

An illustration of salvaging techniques in the early 18th century from a treatise on salvaging by Triewald. (Source: Wikimedia Commons).

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the story of the Vasa began to be told through paintings, sculptures, and literature. The ship was depicted in paintings and sculptures, and its story was retold in novels and plays. The Vasa became an important part of Swedish cultural heritage, and it was seen as a symbol of the country's resilience and determination.

The Salvage of the Vasa Although the sinking of the Vasa was a tragedy, it presented a unique opportunity for a grand-scale modern-day salvage operation. The ship had sunk in relatively shallow water, and its location was well known. From 1957 to 1961, almost 333 years after the ship sank, the Swedish navy undertook a huge salvage operation to raise the Vasa from the seabed.

Several possible methods for recovering a sunken ship were suggested in the early 1950s, including filling it with ping-pong balls and encasing it in a block of ice. However, the method ultimately chosen was the same one suggested immediately after the ship sank.

Divers getting dressed at the Vasa salvage, 1959. (Source: Picryl).

The salvage operation was a massive undertaking that involved a team of divers, engineers, and archaeologists. Over a period of two years, divers worked tirelessly to create six tunnels beneath the ship to secure steel cable slings, which were then attached to lifting pontoons at the surface.

The diver comes out of the water with finds from Vasa, which he hands over to the Fälting diving base. 1959. (Source: Picryl).

This work was extremely hazardous, as the divers had to use high-pressure water jets to cut tunnels through the clay and remove the resulting slurry with a dredge, all while operating in total darkness with hundreds of tons of mud-filled ship overhead.

A find from the Vasa, 1959. (Source: Picryl).

The risk of the wreck shifting or settling deeper into the mud and trapping a diver underneath was a constant concern. Additionally, the almost-vertical portions of the tunnels near the side of the hull could potentially collapse and bury a diver alive. Despite the perilous conditions, more than 1,300 dives were conducted during the salvage operation, without any major accidents occurring.

Vasa's figurehead, designed as a lion. The lion's mane still shone with gold when it merged from the seabed. 1959. (Source: Picryl).

The salvage of the Vasa was a remarkable achievement that demonstrated the skill and expertise of the Swedish salvage team. The ship had been lying on the seabed for over 300 years, and it was in remarkably good condition. The team was able to recover a vast amount of information about the ship's construction and design, and their findings have been invaluable to historians and naval architects.

Royal ship Vasa on the way into Beckholmen's dry dock, 1961. (Source: Wikimedia Commons).

Swedish warship Vasa, finally in the dry dock. (Source: Picryl).

Swedish warship Vasa, finally in the dry dock. (Source: Picryl).

The Legacy of the Vasa The sinking of the Vasa was a tragedy, but the salvage operation that followed was a triumph of ingenuity and perseverance. The ship has now become a symbol of Sweden's rich naval heritage, and it is one of the country's most popular tourist attractions. Vasa is the world's best-preserved 17th-century ship and the most visited museum in Scandinavia.

The Vasa also has a broader significance in the history of shipbuilding. The investigation into the ship's sinking and the salvage operation that followed led to important changes in the design and construction of ships. The lessons learned from the Vasa have been incorporated into the design of modern naval vessels, and they continue to influence shipbuilders around the world.

Comments